A Blog Series from the CSU Network

A Blog Series from the CSU Network

Nearly half of CSU students are from low-income families. With the rising costs of living, these students face a dilemma each semester: whether to continue to pay the costs of college or stop out and pursue a full-time job. This is the second blog in a series focusing on actions that CSU faculty and staff can take to encourage their programs and campuses to address the needs of low-income students and support them in finishing their degree.

For many low-income CSU students, stopping out of college to accept a full-time job can appear appealing. Many of these students are taking on debt for the first time, working odd hours in a part-time job, studying when they can, and worrying about paying for food, rent, books, and other necessities. Stopping out to accept a full-time job can bring these students a bigger paycheck than their part-time job provides, with the potential of supporting family members, paying off debts, and being able to pay for basic living expenses. With a job market that’s booming now, why should these students stay in college for multiple years and risk graduating at a time when the economy may be heading downward?

Myths about the Value of a College Degree

Students facing these legitimate concerns may be particularly vulnerable to myths and memes underrepresenting the benefits of a college education or flat-out stating that college is a scam. What’s worse, these myths appear to be gaining traction. A survey in 2023 by the Wall Street Journal and the University of Chicago found that a majority of Americans now believe that a four-year degree is not worth the cost. This represents a change from previous surveys showing confidence in the value of a degree.

Students facing these legitimate concerns may be particularly vulnerable to myths and memes underrepresenting the benefits of a college education or flat-out stating that college is a scam. What’s worse, these myths appear to be gaining traction. A survey in 2023 by the Wall Street Journal and the University of Chicago found that a majority of Americans now believe that a four-year degree is not worth the cost. This represents a change from previous surveys showing confidence in the value of a degree.

Research on the Value of a College Degree

Despite recent shifts in public attitudes, the facts have remained consistent about the value of a college degree. Researchers have found that, on average and over time, students with a bachelor’s degree earn:

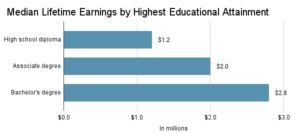

- Higher pay. Those with a bachelor’s degree earn substantially more over their lifetimes than those without the degree. These data are based on analyses by Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce, based on the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey from 2009 to 2019.

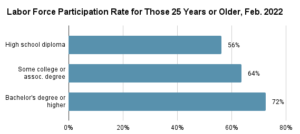

- Greater employability. Those with a bachelor’s degree are more likely to be employed than those without a degree. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the labor force participation rate for those with at least a bachelor’s degree was 72% (in Feb. 2022, the most recent data), compared with 56% for those with a high school diploma or GED. Those with a bachelor’s degree had about half the unemployment rate (2.2%), compared with those with a high school diploma (4.5%).

- Upward mobility. College graduates are also more likely to own a home and less likely to be in poverty, according to the Public Policy Institute of California.

- Brighter options in the future. In surveys, nearly 9 out of 10 employers (87%) say that a college degree is “definitely” or “probably” worth the investment. Currently, two-thirds (68%) of jobs in the U.S. require education or training beyond high school, according to the Center on Education and the Workforce. By 2031, almost three quarters (72%) of jobs will require more than a high school diploma—and 42% will require at least a bachelor’s degree.

The Value of the CSU in Particular

CSU graduates are getting a particularly good bang for the buck compared with those graduating from other higher education institutions. The relative value of a four-year degree, besides depending on the benefits that accrue over time, also depends on the cost of attendance, the earning power of the degree, and the economic and social mobility of the graduates. CSU campuses perform very well on these and related measures.

For example, all 23 campuses of the CSU ranked within the top 30% of universities in Washington Monthly‘s 2023 list of the “Best Bang for the Buck” schools in the West (which ranks institutions based on the above kinds of factors). The CSU dominated the top spots, with four CSU campuses ranked in the top five and seven in the top ten. Similarly, all 23 campuses were featured in CollegeNET’s “Social Mobility Index” for 2022, which measures the extent to which a college educates low-income students, provides lower tuition and fees, and graduates them into well paying jobs. On the Social Mobility Index, four CSU campuses were ranked in the top ten nationally.

What this Means for Middle Leaders

The data referenced above regarding the value of a bachelor’s degree do not mean that all is well for university graduates, even in this flourishing job market. A report published in February 2024 found that over half (52%) of four-year graduates in the U.S. remain “underemployed” one year after graduation, meaning that they have not landed a job that requires a degree. Even more disconcerting, 45% are still underemployed a decade after graduating. This suggests that faculty and staff have a role to serve in strengthening career engagement, internship, and workforce-based programs for students before they graduate.

Moreover, considering the myths that are prevalent about the value of a degree, CSU faculty and staff cannot assume that students know the financial and other benefits of college over the course of their lives. This may be particularly the case for first-generation college students and those students whose lives are not surrounded and influenced by college graduates. Beyond imparting their own subject expertise to students, faculty and staff can help students identify the skills they are learning in their courses and how they apply to various careers in the short- and long-term.

Consider these kinds of interactions with students and/or colleagues:

- Research questions. How much do you and your colleagues know about low-income students in your program or department? What share of students in your program/department:

- Receive Pell Grants? Access basic needs programs?

- Work part-time? Work full-time?

- Access career resources? Participate in paid internships or other work opportunities organized or sponsored by your program/department?

Does your program/department have access to student surveys assessing the needs and eliciting the perspectives of low-income students regarding services they have received or would like to receive, particularly those who work? How can you connect with colleagues to get these types of information?

- Campus resources. What resources are available—including within academic departments, at the library, and at a career center—to provide students with information about:

- Career options, employability, and potential income for various majors or fields?

- Existing internships or partnerships associated with fields and degrees they are pursuing?

How can you connect with your colleagues to ensure that basic information about these resources is provided regularly to students, including taking time in class to discuss these issues?

- Information sharing. How can you provide students with basic information about:

- The value of college over their lifetimes (such as the graphs included in this blog); and

- The value of their education now, as they are pursuing it (such as the skills they are mastering and could put on their resume currently)?

How can you encourage students to research careers in their potential field and discuss potential impacts on their lives and their families?

- Leadership stories. Faculty and staff can help students visualize and actualize their own career paths. What on-going opportunities can you create (in class, office, or department settings) to engage with students about their aspirations after college? Two key components involve:

- Sharing your own leadership story (along with colleagues or community/business partners, where appropriate) about how you came to the position you’re in; and

- Providing ways for students to discuss and share with each other their leadership stories that brought them to college and their aspirations after college.

- Structural change. How can you work with colleagues to create on-going opportunities for students within your program, office, or department to learn about and recognize the value of their education over the short- and long-term? For example:

- How can you and your program, office, or department engage students and former students as mentors for entering students regarding career and resume development?

- How can alumni serve as mentors and professional contacts for students who are graduating?

- How can you and your program develop ways for students to network with professionals in their field of study, including internship programs?