First-in-their-family college students account for nearly one-third of students enrolled across the California State University (CSU) system. Moreover, students who do not have a parent with an undergraduate degree have constituted the majority of the CSU student population since 2010. Though first-generation students represent a large share of CSU enrollment, completion is a different story. First-generation completion rates have hovered between 10- to 15-percent lower than the rates of their continuing generation peers since the mid-2000s, with first-generation students of color seeing degree completion at the lowest rates among their peers. How can faculty, staff, and administrators support efforts such as Graduation Initiative 2025 to help facilitate a reduction of the equity gap between first- and continuing generation college students? Toward answering that question, we propose pausing to think about the function and meaning of the first-generation label. This blog is the first of a three-part series on supporting first-generation student success in the CSU system.

Who is a first-generation college student and why do technical definitions matter?

There is no universal definition of a first-generation college student. A 2018 study used eight different definitions of first-generation to analyze the college-related activities of over 7000 students: researchers found that between 22- to 77-percent of students in the sample could be considered first-generation depending on the definition used. As established by the Higher Education Act of 1965, the federal government considers a student to be first-generation if both parents do not hold a four-year degree. In contrast to the federal definition, the CSU system defines a first-generation student as one whose parents did not attend any college. Programs within the CSU that are not beholden to any particular institutional mandate often choose the definition that suits their goals.

The lack of a consistent definition holds practical implications for students who would benefit from participating in programs and services aimed at supporting first-generation student success. Perhaps the biggest problem created by inconsistent definitions is the potential for exclusion: restrictive definitions of “first-generation” applied at the program level inherently cut people off from opportunities. Moreover, students—particularly those in the early years of their college careers—who may not be clear about whether their family situation qualifies them to be considered first-generation may self-select out of seeking available services. While it is not probable that a single unifying definition of first-generation will ever be applied consistently, the most equity-minded approach to building programs and resources will always be the most inclusive.

But who is a first-generation college student?

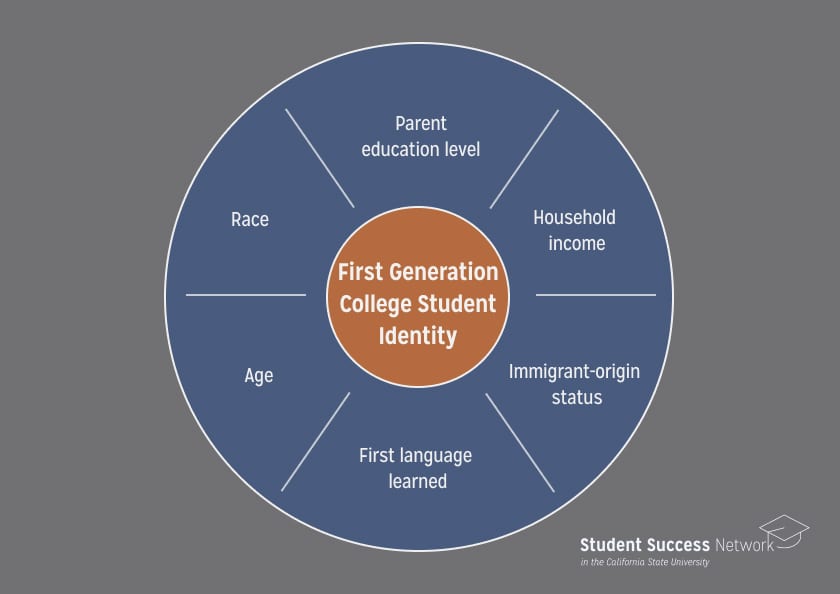

Parental educational status underscores formal definitions, but first-generation is best understood through an intersectional lens. Compared to their continuing-generation peers, first-generation students are more likely to speak English as a second language and pursue their undergraduate degree at an older age. By comparison, more students of color tend to be first-generation than continuing-generation. Moreover, first-generation college students are far more likely to come from low-income households than their continuing-generation peers.

The first-generation label is a marker for a combined set of characteristics that affect a student’s college trajectory. For instance, compared to higher-income, continuing-generation college students, low-income, first-generation students are four times more likely to leave college after their first year. From a data standpoint, work is being done in the CSU to better understand how the intersecting characteristics of first-generation students impact success. Moving data insights to action at all levels—institutional, programmatic, and interpersonal—is key to supporting first-generation students and closing equity gaps. The next piece in this series will focus upon translating knowledge into action.

All uses of the term “first-generation” in this post are associated with the CSU definition, unless otherwise stated.